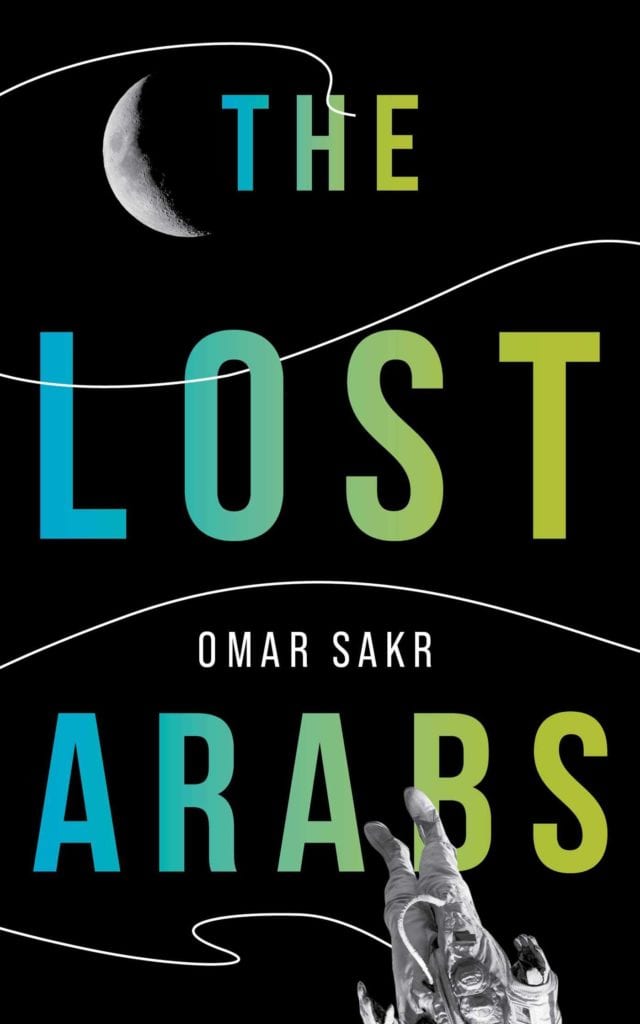

Omar Sakr is an award-winning poet whose work focuses on the queer identity, place, belief, and the edges and borders of self and land. Self-described as the bisexual Muslim son of Lebanese and Turkish migrants, his sense of culture and perspective, and his questions around what it means to be a part of something is the very blood of his book, The Lost Arabs.

Content & Themes

The Lost Arabs opens with the line, “People don’t seem to understand,” but by the end of the book, the reader does. The reader comes away understanding so much of what Sakr is sharing: his views of space, place, self, sexuality, our world.

There are poems of home, poems of religion, and poems of how one fits into the larger space. Yes, they are Sakr’s story, but the poems are so honest and available that you can find remnants of yourself in all of them.

Voice & Tone

With startling attention to detail and lineation, this is a musical poetry that knows its voice. You can tell Sakr is devoted to every word, every line, truly crafting the shape and sound of a poem with care.

Sakr’s voice is rich. That it to say, it’s not opulent or baroque or drenched in metaphor. The ideas are easy enough to follow, but the beautiful and deliberate imagery and the attention to merging the narrative with the poetic pulls you into an emotional embrace. From This Is Not Meant For You, even this small stanza pulls you into itself. You can taste the bread, smell the smoke, feel the deep cultural resonance that the poet shares:

The driver releases me

onto Sydney Road, a replica of home,

all the Leb bread, smoke, & men.

In House of Beirut, a poem written as a prose-style block (which facilitates Sakr’s often-narrative style), we fall easily into Sakr’s mind, as if we were raised in his house, his family, his lineage. The poetry is so all-encapsulating that you can’t help but simply fall in and disappear into the words. It is a book of truth, pain, and beauty — and it inspires empathy and connection in its reader.

Once, my ancestors would have been united—in name if nothing

else—knighted by the conqueror’s blade as Ottoman. Not Lebanese,

not Turkish. I cannot imagine the ease of being only one thing.

I am sure this too is a fantasy. In Beirut, a memorial is taking

over a house where every bullet hole has been given a name,

a shrine to the violence that (r)ejected my family. Only in light

of this can you call it Paris, otherwise leave that imperial shade

alone. They say people are afraid to speak of the civil war lest

it spark back to life. The war is not taught. Who knew my family

have followed official policy for years? They will be devastated

to hear it. All my knowledge is myth-made, media-driven,

an inherited memory washed by a generation of tired hands…..

Overall

In the end, these superbly-crafted poems are some of the best you’ll read. This is a poet whose work contributes to the greater fabric of what it means to be alive. Just read this passage from On the Way to Sydney. Try to pretend that you don’t feel every single perfect word.

I am a child again spilling free in Lurnea,

an Arab boy among others, a boyhood of colours,

locust mouths descending on the mall,heavy with need. Heavier with regret. Or

desire.

To stay up-to-date, make sure to keep an eye out for more of little infinite’s featured content as we celebrate poetry, books, and this beautiful hot mess we call life on Instagram and Twitter.

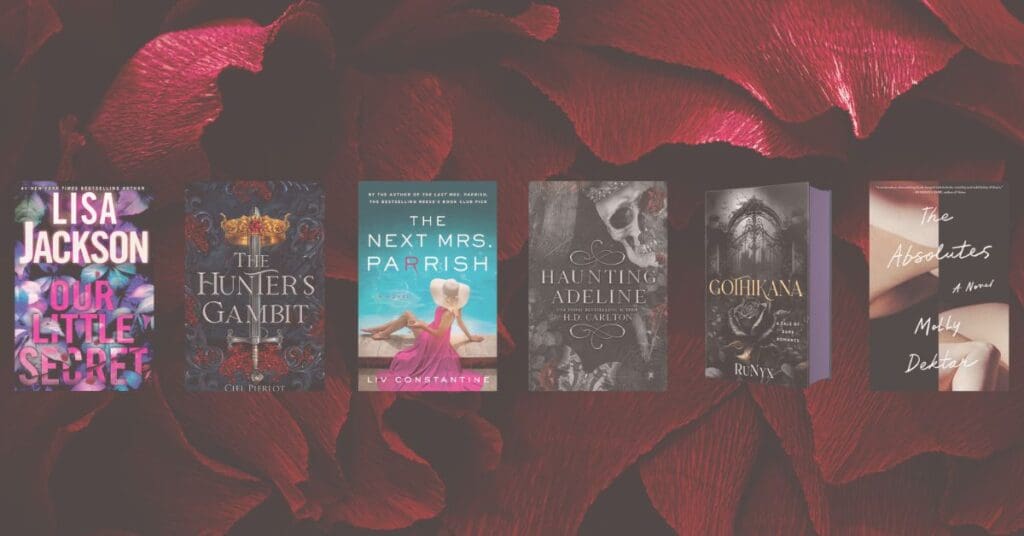

Shop This Article: