Poetry is at the butt of plenty of jokes — mostly about it being overly emotional (“oh, go write a poem about it”) or about poets, you know, being broke. I’ve experienced tons of confused, snide (and some surprisingly nasty) comments, and they’re usually reductive or just plain cliche at this point:

So, you went to school for poetry — how do you pay your bills?

I can’t imagine that you make any money working as a poet.

What does a poet even do?

Well, we all know there’s no money in poetry.

Wait, so you, like, have a book? Does you make money from it or is just a side thing?

Oh, I wrote a poem once! I should take it up again for fun.

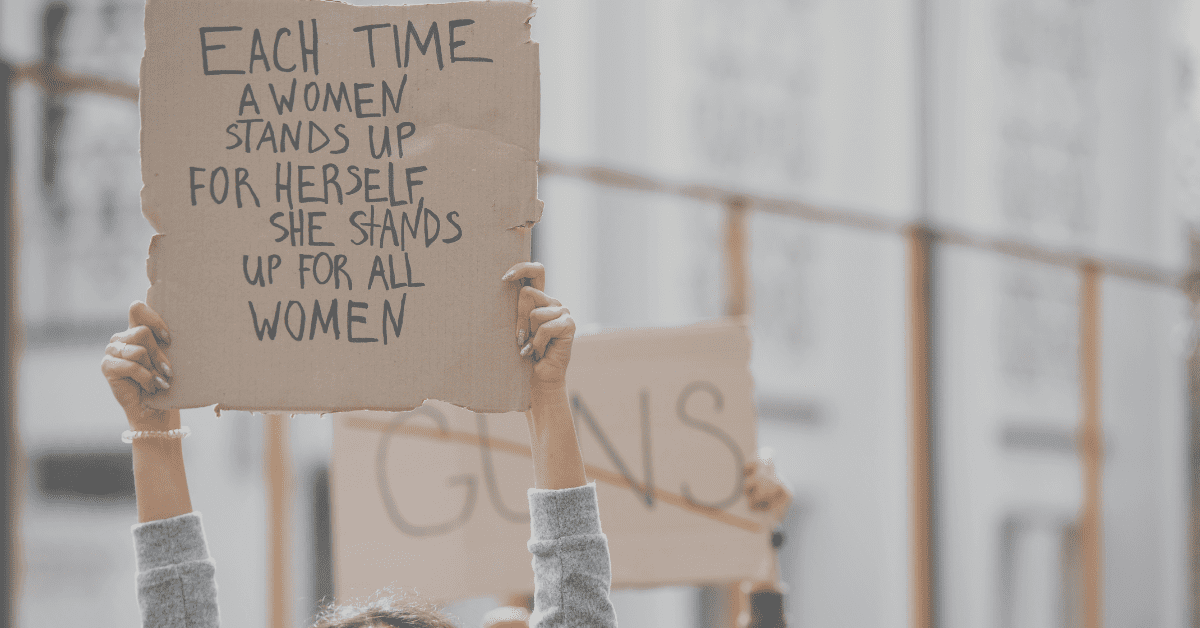

It’s almost as if — wait for it! — poetry isn’t inherently valuable unless it earns money. And that’s a problem. Because poetry is valuable. It’s valuable existentially, socially, politically, spiritually, and culturally.

That it is still sorely undervalued monetarily is deeply juxtaposed by the fact that poets have long been immortalized and revered (while their works are turned to for comfort, wisdom, and truth during periods of unrest or stagnation or renaissance).

Cue the moment Jodie Foster cries out, “They should have sent a poet!” in the movie Contact. Seriously, poets make everything better.

Those remarks above are also awful because poetry is work. Many poets, even if they have a day job in an office, don’t consider their poetry practice a “side thing” at all. In fact, many poets consider themselves poets first and employees second. In a sense, our jobs — the things that pay our rent — are our true “side things.”

Poetry doesn’t pay my rent, but I will always be a poet. It’s part of my identity. And money doesn’t make something more or less real to me.

Many poets view their poetry this way. Poets write, edit, submit, publish and promote their work. Poets go on tours to give literary readings, run presses and literary journals — usually or very little to no pay, work in academia teaching poetry, lead poetry workshops for at-risk youth, incarcerated individuals, and other marginalized communities, manage well-known poetry festivals, and, you know, write poems for Beyoncé or work for Elizabeth Warren. (Go Warsan Shire and Camonghne Felix!).

And most of us do that while holding down a day job or raising kids. It’s not a side hustle. It’s a job and a passion and a love affair with language that doesn’t earn a liveable wage for most of us. Because many nations and cultures respect art — but not enough to fund it. They want it to simply appear, but they don’t want to nurture it. Because they don’t think it is tangible. They think it has no result or promise. It’s not efficient. It’s not profitable or scalable.

Except, it kind of sort of it all of those things. It gives more than we know, especially in the long-term.

For many other people, writing poetry is a hobby or a self-care tool. It’s a way of exploring your creativity and relaxing your mind and finding ways to give language to your deepest, most inner thoughts and feelings and fears. How is that not also valuable?

In short, poets and poetry majorly contribute to the artistic fabric of our society.

But how do poets make money?

Despite the fact that writing poetry generally doesn’t secure a poet their rent, many poets do make money from their craft. And I think that’s worthy of celebration — because they deserve it.

For one, some poets work as program coordinators for writing programs or as editors for magazines like Poets & Writers. So, yes, there are some salaried jobs in poetry or poetry-adjacent fields.

A piece on the economics of poetry was published in the HuffPost, which may be illuminating — but doesn’t reflect every poet’s experience.

I talked with dozens of poets on Facebook and Twitter about how they make money. Most mentioned that they were paid for poems published in lit magazines, or that they self-published books and sold them at conferences and fairs. Some said they taught poetry workshops.

Then there were some interesting poetry jobs, too: “My church pays me a small stipend to be their Poet in Residence. I contribute poetry, prayers, etc to worship services, teach classes (e.g. Biblical poetry), and host events,” poet Dianne Turgeon Richardson said.

Another poet told me they sell ad slots within their poetry. When they perform the poetry, they’ll talk about the advertiser within the poem. Pretty clever, huh?

One poet told me they’d read a book called, “How to Make a Living as a Poet” by Gary Mex Glazner. It offered ideas like working with hotels to write poem-fortunes for the hotel rooms.

Another poet told me, “I’ve found that many university programs love a creative pitch, so i’ve been doing some really rewarding (and surprisingly well-paying) gigs doing university workshops.”

I’ve made money from my poetry, too. In 2017, I co-wrote a poetic ritual for a two-day Halloween-time festival, Into the Veil, produced by Atlas Obscura. During this festival, we walked listeners through a poetic ritual, complete with candles and audience participation — all in an effort to get people comfortable with the idea of death and the beauty around it.

That poem you hear in this video? It’s me and my co-host:

I’ve also taught numerous poetic workshops, I’ve performed for poetry cabarets in different cities and countries. I’ve been paid to write poem-descriptions for Valentino, who were developing a perfume line.

And, like some poets, I have earned money from the royalties from my published poetry books, too (although not every poetry book has a royalty-yielding contract, and even then, it’s not much in earnings). A royalty payment is a percentage of payment owed to a poet with each book sale. The fact is, though, many poetry presses make such little money that it’s hard to provide royalties.

So what about Instagram poetry? Some people argue that “Instagram saved poetry” but I think we all know that’s ridiculous. Poetry didn’t need to be saved; so long as humans have emotions, poetry will never be dead. It doesn’t require technology to flourish.

That said — and this is a big deal — #Instapoets are selling hundreds of thousands of copies of their books — and selling some pretty pricy merch while they’re at it. They not only sell their books (which you’ll find on sale at places like Urban Outfitters), but they get sponsorships and campaign deals, too.

Everyone has bills and debts to pay — and your work is inherently valuable in all sorts of ways. My hope is that by sharing this information, we’ll normalize poetry as a monetarily valuable craft.

Want some more ideas for making poetry more profitable for you? Here you go:

Taught poetry workshops to diverse communities: adult literacy centre, lockdown facilities for at-risk youth, a centre for pregnant/young moms, online video-conferencing sessions, elementary & high schools, all-age blackout poetry workshops & I read poetry to folks in elevators!

— Greg Santos (@moondoggyspad) April 25, 2019

All new arrivals/subscribers to my Patreon get a poem (form my choice) of either the first time we met OR if we have not – a poem based on my interactions with them online.

— Dr. Rhonda Baughman (@Dr_Baughman) April 24, 2019

I sell annotated copies of my books which is basically me charging extra to as i say mark them up with my thoughts pink ink teenage diary style. This entire year I have been annotating books nonstop.

— Kristin Garth (@lolaandjolie) April 24, 2019

In the end, writing poetry is a beautiful, strange, otherworldly art. My hope is that poems will have the same value as songs or works of art.

The liminality of the poet’s life is interesting because we are at the intersection of invisible and immortal, and it’s centered between art and entertainment and healing. Our work will always reflect the true nature of humanity, and yet we rarely receive recognition. For example, How many pop stars can you name? How many poet laureates can you name?

Poets: Know that you’re already valuable — with or without a price tag attached to your work.

Feature Photo by Thought Catalog on Unsplash.