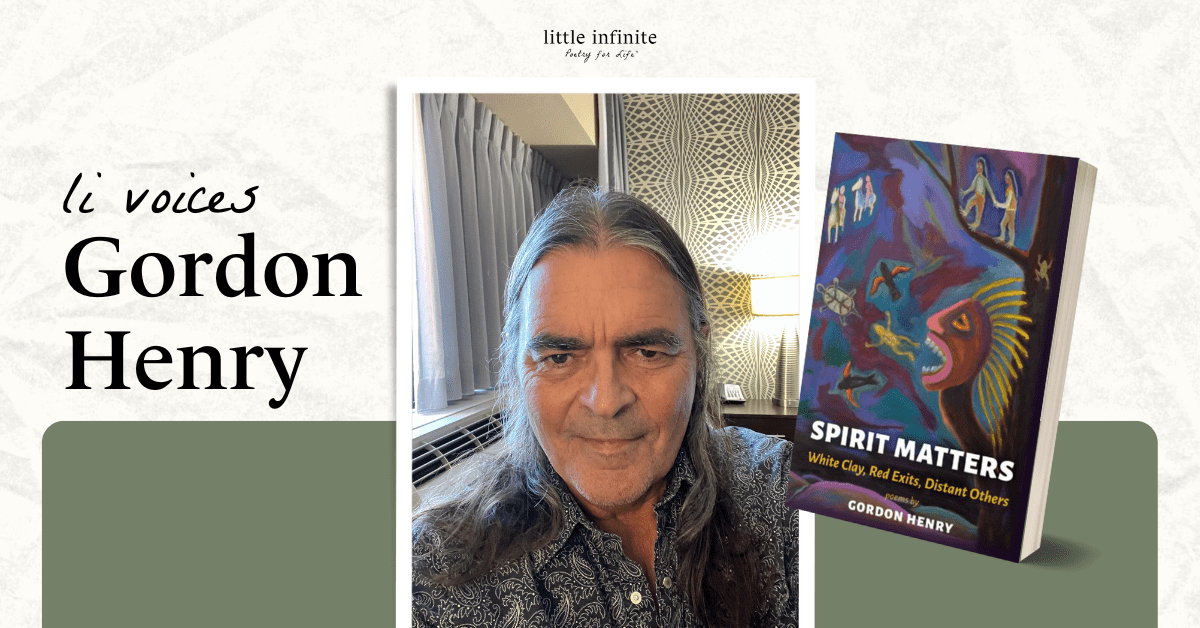

Get to know the American Book Award-winning Ojibwe author and poet Gordon Henry from our exclusive interview.

Be sure to check out his newest collection, Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others.

little infinite: How did you get into poetry and when did you know poetry would be the writing outlet for you?

Gordon Henry: I started writing in private mode, just after high school. I was writing little fragments, I considered some of them poems, but didn’t know since I had never had any formal training or creative writing courses. In fact, I never showed anyone my writing for six or seven years or so. I would write on notepads, then deposit paper drafts in a dresser drawer. Most of those pieces are long gone. I kept writing, privately after dropping out of college and was working full-time. I wrote with more intensity, then after I re-enrolled in college, even though I was a business management major. In my downtime, at the university I would drift into the library and read books on mysticism and poetry, rather than in my chosen field of business. I eventually took an intro to creative writing, a poetry class, with poet Donald Cummings. He encouraged me to continue writing, as did an instructor who met with me informally through a student work-study position. His name was Geoff Gajewski. He too was a poet. He went through some of my writing with me and offered some pointers and directed me to some readings in contemporary poetry.

After graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Business Management, I went west looking for work. I landed a job as a bookkeeper for the Yaqui Tribe and kept writing. While working I applied to graduate school creative writing programs, was accepted at the University of Arizona, Central Michigan University, and Michigan State University. I chose Michigan State since they offered me a fellowship. While there I took creative writing courses, with poet Diane Wakoski and fiction writer Sheila Roberts.

Both affirmed what I

little infinite: Poetry for Life™ is little infinite’s mantra, we’re about making it easier to carry poetry through different phases of your life. Poetry for Life can hold sentiment in various aspects according to the person, which is why we love it. What does “Poetry for Life” mean to you?

G. Henry: Poetry for life in the most basic sense means we may continue to write poetry to some beautiful, holy, extended end that is our life and our life in the poems we have written and those that remain unwritten. Further, we may listen, see, appreciate life to that end, with the eyes and ears and tastes of life that brought us to poetry.

little infinite: If you could describe this collection (or your writing style) in three words, what would those words be and why?

G. Henry: Loss, Family, Connection

little infinite: As a child, what did you want to be when you grew up?

G. Henry: Probably a baseball player, or a thespian, or a singer, or all of the above.

little infinite: What is the biggest risk you’ve taken with your writing? What did you learn from that experience?

G. Henry: The biggest risk involves disclosure of the unclosed way we process experiences that continue to inform our heartache and longing. Processing that through imagery, sense remembrance, embrace of loss, re-ignition of small flairs of pain and fires of disappointment. To share such is to fly into risk in very particular ways that may involve additional risk, in that you just don’t know if people will or can connect with it. Is it clear enough? Good enough? Even though it’s all you’ve got to give at the time?

I also embrace structural risk as a way of challenging myself. I may blow up syntax or punctuation, points of order and clear junctures of connection.

little infinite: What book(s) are you currently reading

G. Henry: I read mostly what I’m teaching in classes. At this time, Native poets in the Living Nations, Living Words anthology. A few memoirs and novels for a Re-mapping Tribal Narratives class. I’ve got a bedside table with some philosophical texts, GIS manuals and a host of poetry and fiction books. I just picked up Michael Harper’s Dear John Coltrane, I’m digging back into Wilson Harris’s Infinite Rehearsal, browsing a number of texts, Calvino’s, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, Manifestation Wolverine, by Ray Young Bear and Infinite Ash, by Victor Rodriquez Nunez and Creative Imagination in The Sufism of Ibn Al Arabi, by Henri Corbin, Basil Johnston’s, The Manitous, just a lot of great inspiring work

little infinite: What would you say is your greatest accomplishment as an author/poet so far?

G. Henry: Getting published when I never thought I would.

little infinite: What does the title of this book mean to you? Tell us about how you came up with the title, Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others.

G. Henry: Titles are always tough for me. I wrestled with a number of possibilities for a few months, such as White Clay, Red Exits, for one, Relative X’s, for another Departure’s Borne Reflect, a flat Spirit Matters, was the initial choice, as a play on matter as some kind of materiality and matters as concerns, or things that have happened to us. Chiaaboos at the River, was another possibility.

little infinite: How did this collection speak to you differently? What was the most surprising phase of creating this collection?

G. Henry: It spoke to me as less playful, with less playful humor than other work I’ve done. It was surprising how quickly some of the poems came to me and developed. The organization of the whole manuscript was enlightening to some degree. I had to throw out a lot of work I might have included. Not sure I got it quite right. (That’s not a surprise.)

little infinite: What is your creative process like? If you could dish on the most unique part of your writing process, what would it be?

G. Henry: I think it would have to be the continuing internal, yet to be written, sometimes unwritten, work that flows through me. The difficulty I have in finding time and space to convert that to material text is often unresolved. I need more solitude, it seems, a month or two out on the limb of a tree, with meals delivered by crows or sunbasket, under the influence of the music of swans, under the spell of light and air that breaks open the fissures of memory, to bring me back to a longing I have yet to know fully or reconcile.

little infinite: If you could give a new writer one piece of advice for starting, what would that piece of advice be? Why does this piece of advice personally stand out to you?

G. Henry: Work through deep memory, the spaces, people, the large and small of it, the near and distant. Try to work with the images coming through that memory, by extending, bending, re-coloring, re-imagining, whatever it takes to move the memory to a place on a page. And/or let language carry you to what comes next. Not very good advice, but I think it will lead to some path that might be worth following . . .

Purchase Spirit Matters: White Clay, Red Exits, Distant Others

Gordon Henry is an enrolled member/citizen of the White Earth Anishinaabe Nation in Minnesota. He is also a Professor in the English Department at Michigan State University, where he teaches American Indian Literature and Creative Writing. He serves as Senior Editor of the American Indian Studies Series at Michigan State University Press. In 1995, Henry received an American Book Award for his novel the Light People and his poetry, fiction and essays have been published extensively in the U.S. and Europe. In 2004, he co-published an educational reader on Ojibwe people with George Cornell. In 2007, Henry published a mixed-genre collection, The Failure of Certain Charms, with Salt Publishing. More recently Henry’s writing has appeared in, Bob Seger’s House, (Wayne State University Press); Iperstoria, a literary journal from the University of Verona, Italy; Revolucion: A Cuban Journal, of Havana; New Poets of Native Nations; Poetry; Wassafiri; and When the Light of the World was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through (2020) and Living Nations, Living Words (2021)–two poetry anthologies edited by Joy Harjo. He lives in Empire, Michigan.

To stay up-to-date, keep an eye out for more of little infinite’s featured content as we celebrate poetry, books, and this beautiful hot mess we call life on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.